A thread on one of the Internet forums reminded me of an interaction I had with a fellow a couple of years ago. His room was just under 10'X10', HO scale, double-track mains, transition era. Not a huge space, but workable.

Then he told me about his standards: only #8 turnouts would be permissible, along with a 36" minimum radius. His reasoning? It would be more like a "real railroad" and he wanted his layout to be recognized as uniquely realistic.

Okey-dokee. But one doesn't have to be a very experienced designer to see that there is darned little straight track left after placing 36" circles around a 10X10 foot space.

I suggested modulating his standards -- perhaps one scene with broad radii and turnouts and then using more compact standards elsewhere. Nope, that just wouldn't do for him. We both recognized that I wasn't the right person for the job and he continued his quest for a designer who could alter the space-time continuum.

Layout design standards should not be status symbols. Broad curves and #8 or larger turnouts look great – but in the more modest spaces typical of most model railroads, they create the need to significantly reduce the number and size of other layout elements possible.

If reducing operating potential or the number of railfan scenes in exchange for broader curves and turnouts is an acceptable trade-off, more power to you. But as John Armstrong noted, too large a minimum radius can be just as deleterious to a design as a minimum radius that is too small.

Standards should follow the concept, purpose, and space available for a layout, not lead them. That's why I hate to see folks with more modest spaces declaring #8 or #10 turnouts as their sine qua non even before developing their overall vision for the layout.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Thursday, March 04, 2010

Kidding Yourself

I work on more layout designs and track plans than most people -- dozens and dozens, in fact, in the last six years. These plans are for many different spaces, concepts, and scales. And yet, I'm still sometimes surprised when I start a new project at how little of what my clients and I have conceptualized will actually fit -- when drawn to scale.

Curves, turnouts, straight sections to ease S-curves, horizontal and vertical easements, and on and on. Each of these takes more space than I would like. And certainly more than most people think.

That's why I just shake my head when I see what some people post in forums. They prattle on for months (or years!) about the fabulous layout design on which they are working: Steel mills, division point yards, car floats, auto plants. And all in 10'X10' in HO.

OK, that's a slight exaggeration, but only slight. Bottom line, if you haven't rendered the major elements to scale in some fashion, you're kidding yourself. That can be CAD, paper templates, or a to-scale sketching technique like John Armstrong's squares. Any of these can provide a quick (and usually sobering) reality check.

But these empire builders carry on, regaling their rapt forum audiences with tales of how great it's going to be. And they often illustrate their posts with photos of clutter-filled corners, stacks of unbuilt Blue Box kits, and horizontal "benchwork" surfaces piled high with soda cans, stacks of magazines, and other detritus.

Now there is a time, early in the design process, when it's a very good idea not to be constrained by scale. However, that's an early conceptual phase and reality must eventually be reckoned with.

So if you've been talking about your "design" for a couple of years, it's time to face the facts. If you haven't yet drawn your space and the major elements to scale, you're not working on a layout design; you're working on the idea of working on a layout design.

The Aqua Velvets' CD Nomad has been in heavy rotation lately at LayoutVision headquarters. A different take on modern instrumental surf music, with many of the tunes having a slightly darker tone (surf noir, if you will). Just for variety and whimsy, some other styles are mixed in, including what sounds like a rumba and a bit of reggae flavor. The playing is crisp and toneful, without the speed-for-speed's-sake that burdens some instro surf music.

The Aqua Velvets' CD Nomad has been in heavy rotation lately at LayoutVision headquarters. A different take on modern instrumental surf music, with many of the tunes having a slightly darker tone (surf noir, if you will). Just for variety and whimsy, some other styles are mixed in, including what sounds like a rumba and a bit of reggae flavor. The playing is crisp and toneful, without the speed-for-speed's-sake that burdens some instro surf music.

And there are plenty of conventional surf sounds, too, played with a respect for the tradition but an eagerness to stretch a bit musically. The kind of surf music that might make you remember fondly those sunny days at Hermosa Beach -- even if you've never been out of Nebraska.

Curves, turnouts, straight sections to ease S-curves, horizontal and vertical easements, and on and on. Each of these takes more space than I would like. And certainly more than most people think.

That's why I just shake my head when I see what some people post in forums. They prattle on for months (or years!) about the fabulous layout design on which they are working: Steel mills, division point yards, car floats, auto plants. And all in 10'X10' in HO.

OK, that's a slight exaggeration, but only slight. Bottom line, if you haven't rendered the major elements to scale in some fashion, you're kidding yourself. That can be CAD, paper templates, or a to-scale sketching technique like John Armstrong's squares. Any of these can provide a quick (and usually sobering) reality check.

But these empire builders carry on, regaling their rapt forum audiences with tales of how great it's going to be. And they often illustrate their posts with photos of clutter-filled corners, stacks of unbuilt Blue Box kits, and horizontal "benchwork" surfaces piled high with soda cans, stacks of magazines, and other detritus.

Now there is a time, early in the design process, when it's a very good idea not to be constrained by scale. However, that's an early conceptual phase and reality must eventually be reckoned with.

So if you've been talking about your "design" for a couple of years, it's time to face the facts. If you haven't yet drawn your space and the major elements to scale, you're not working on a layout design; you're working on the idea of working on a layout design.

The Aqua Velvets' CD Nomad has been in heavy rotation lately at LayoutVision headquarters. A different take on modern instrumental surf music, with many of the tunes having a slightly darker tone (surf noir, if you will). Just for variety and whimsy, some other styles are mixed in, including what sounds like a rumba and a bit of reggae flavor. The playing is crisp and toneful, without the speed-for-speed's-sake that burdens some instro surf music.

The Aqua Velvets' CD Nomad has been in heavy rotation lately at LayoutVision headquarters. A different take on modern instrumental surf music, with many of the tunes having a slightly darker tone (surf noir, if you will). Just for variety and whimsy, some other styles are mixed in, including what sounds like a rumba and a bit of reggae flavor. The playing is crisp and toneful, without the speed-for-speed's-sake that burdens some instro surf music.And there are plenty of conventional surf sounds, too, played with a respect for the tradition but an eagerness to stretch a bit musically. The kind of surf music that might make you remember fondly those sunny days at Hermosa Beach -- even if you've never been out of Nebraska.

Monday, February 22, 2010

What He Said

I had an interesting project with a client a year or so ago. He was picturing a rectangular layout in a rectangular space that allowed only a minimum of space for rectangular aisles on three sides. Sound familiar?

We had a lot of discussion on the layout footprint and we were able to encourage him to accept a more "organic" shape. In this case, sort of a "boomerang" or "kidney" outline that fit into one corner of the room.

The curving benchwork gave him more room for construction, operation, and maintenance. And I thought it certainly a lot more interesting visually than yet another monolithic rectangle layout.

Although he had to work out some interesting challenges in construction (for example, adding a third L-girder a la Linn Westcott), my client reports that construction is well along; track is laid and wiring is underway.

And how does he feel now about that curvilinear benchwork? In his own words, "… it looks a lot better than a roundy-roundy rectangle!"

[Watch for the layout plan story in a future issue of the commercial press …]

We had a lot of discussion on the layout footprint and we were able to encourage him to accept a more "organic" shape. In this case, sort of a "boomerang" or "kidney" outline that fit into one corner of the room.

The curving benchwork gave him more room for construction, operation, and maintenance. And I thought it certainly a lot more interesting visually than yet another monolithic rectangle layout.

Although he had to work out some interesting challenges in construction (for example, adding a third L-girder a la Linn Westcott), my client reports that construction is well along; track is laid and wiring is underway.

And how does he feel now about that curvilinear benchwork? In his own words, "… it looks a lot better than a roundy-roundy rectangle!"

[Watch for the layout plan story in a future issue of the commercial press …]

Friday, February 19, 2010

The Double (Track) Cross

For the majority of readers who visit this blog (thanks, by the way), this post is of no particular use.

But I see this error over and over again on user-posted track plans, so if it helps only one or two folks before they permanently fasten down their track, it's worth it.

The top configuration in the drawing above is often seen on newcomers' double-track ovals and other areas where double tracks curve into a set of crossovers.

Because the tighter inner end curve feeds directly into an opposing crossover, it creates a possibly troublesome S-curve, especially when shoving longer cars through. The alternative arrangement on the bottom of the drawing offers the same routing flexibility but creates much gentler S-curves.

Note that the same problem can develop when newcomers place an off-the-shelf double-crossover too close to a tight curve, not realizing that one route creates a significant S-curve.

Yeah, I know it's kind of a basic point -- thanks for indulging me.

But I see this error over and over again on user-posted track plans, so if it helps only one or two folks before they permanently fasten down their track, it's worth it.

The top configuration in the drawing above is often seen on newcomers' double-track ovals and other areas where double tracks curve into a set of crossovers.

Because the tighter inner end curve feeds directly into an opposing crossover, it creates a possibly troublesome S-curve, especially when shoving longer cars through. The alternative arrangement on the bottom of the drawing offers the same routing flexibility but creates much gentler S-curves.

Note that the same problem can develop when newcomers place an off-the-shelf double-crossover too close to a tight curve, not realizing that one route creates a significant S-curve.

Yeah, I know it's kind of a basic point -- thanks for indulging me.

Friday, February 12, 2010

Does this yard make me look fat?

Some questions are basically unanswerable; the stereotypical classic is when your spouse asks, "Do these pants make me look fat?"

I have been reminded of these types of unanswerable questions in the last few weeks on various Internet forums. Folks post a track plan for a yard (often a simple mechanical transcription of one of John Armstrong's plans from Track Planning for Realistic Operation). Then they ask, "Is this a good yard plan?"

I dunno. Maybe. Maybe not.

There are quite a few facts not yet in evidence. Where is this yard located in relation to staging, junctions, branches, and other yards (if any)? How many trains will this yard serve in a session? In which direction will most trains run? Will this yard originate or terminate trains? How many trains? What types of trains? How much classification is needed versus simply block swaps? What era?

Without the answers to these and other questions, there's really no way to make an accurate judgment about the suitability of any yard design for a specific layout.

Of course, this doesn't stop the self-proclaimed forum experts from adding their two cents, advising various additions and changes that may (or may not) improve that yard's function in a specific layout.

While the classic Armstrong designs are better than 98+% of what most modelers dream up on their own, I hate to see this kind of unanswerable yard design question receiving so many pat (and patently incorrect) answers.

The right answer ("It depends, let's look at the rest of your layout design and your operations concept.") won't satisfy the typical immediate-gratification help-seekers -- but it is the reality of plausible, efficient, and engaging yard design.

I have been reminded of these types of unanswerable questions in the last few weeks on various Internet forums. Folks post a track plan for a yard (often a simple mechanical transcription of one of John Armstrong's plans from Track Planning for Realistic Operation). Then they ask, "Is this a good yard plan?"

I dunno. Maybe. Maybe not.

There are quite a few facts not yet in evidence. Where is this yard located in relation to staging, junctions, branches, and other yards (if any)? How many trains will this yard serve in a session? In which direction will most trains run? Will this yard originate or terminate trains? How many trains? What types of trains? How much classification is needed versus simply block swaps? What era?

Without the answers to these and other questions, there's really no way to make an accurate judgment about the suitability of any yard design for a specific layout.

Of course, this doesn't stop the self-proclaimed forum experts from adding their two cents, advising various additions and changes that may (or may not) improve that yard's function in a specific layout.

While the classic Armstrong designs are better than 98+% of what most modelers dream up on their own, I hate to see this kind of unanswerable yard design question receiving so many pat (and patently incorrect) answers.

The right answer ("It depends, let's look at the rest of your layout design and your operations concept.") won't satisfy the typical immediate-gratification help-seekers -- but it is the reality of plausible, efficient, and engaging yard design.

Saturday, February 06, 2010

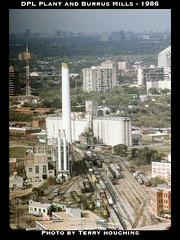

Plans of Steel

Over the years, I've had a few requests for layout designs that included some elements of the steel industry. While I have gleaned enough from back issues of the Railroad Industry SIG's publications and articles published in the commercial press to do a decent job, a couple of recent projects have demanded a more intense focus on the steel industry.

So I'm really grateful that the NMRA arranged for the reprinting of Dean Freytag's The History, Making and Modeling of Steel. It also helps that the book is very focused on the Walthers steel industry models in HO scale and N scale, since most of my clients want to at least start with these kits as a basis for their modeling.

So I'm really grateful that the NMRA arranged for the reprinting of Dean Freytag's The History, Making and Modeling of Steel. It also helps that the book is very focused on the Walthers steel industry models in HO scale and N scale, since most of my clients want to at least start with these kits as a basis for their modeling.

(Between the time I started writing this blog entry and today, I discover that the book is sold out at the NMRA -- sorry about that. Perhaps interested readers will be able to find it from other sources or through inter-library loan.)

One of the nice things about Freytag's approach in the book is that he offers a lot of variations. Whether the modeler's preference is for detailed prototype replication or something more casual, lots of space dedicated to the steel industry or just a corner of the layout, Freytag offers useful advice for all. And he offers these suggestions in a positive and encouraging way that many modelers will find motivational.

Another very helpful part of the book is its focus on explaining in some (although not excruciating) detail the steel making process. Even this modest amount of background makes obvious the flaws in many steel-oriented published track plans.

I understand Bernie Kempinski has a book on the steel industry in the publication process and I'm sure that will be a good resource as well. But I wanted to take a moment to acknowledge Dean Freytag's excellent scholarship and spot-on writing tone, perfect for the modeler. Hopefully the book will become more readily available again.

I've written before about Allman Brothers member and recent Eric Clapton sideman Derek Trucks. I've been enjoying the Derek Trucks Band's most recent album, Already Free. Although the jazz and world music elements are still evident in Trucks' fabulous slide guitar sound, this album seems to me to have more blues and rock influence. Whether it's the easy acoustic shuffle that phases into a driving electric rock riff in "Down in the Flood" or the greasy slide that powers "Get What you Deserve", many of the tunes show a bit more muscle this time out.

I've written before about Allman Brothers member and recent Eric Clapton sideman Derek Trucks. I've been enjoying the Derek Trucks Band's most recent album, Already Free. Although the jazz and world music elements are still evident in Trucks' fabulous slide guitar sound, this album seems to me to have more blues and rock influence. Whether it's the easy acoustic shuffle that phases into a driving electric rock riff in "Down in the Flood" or the greasy slide that powers "Get What you Deserve", many of the tunes show a bit more muscle this time out.

Also welcome to my ears are the vocal contributions of Clapton bandmate Doyle Bramhall II (who also wrote and produced some songs on the album) and Trucks' talented wife Susan Tedeschi. While I enjoy regular vocalist Mike Mattison, I find the variety of vocal styles really accents the wide range of Trucks' playing in this, my favorite Derek Trucks album to date.

So I'm really grateful that the NMRA arranged for the reprinting of Dean Freytag's The History, Making and Modeling of Steel. It also helps that the book is very focused on the Walthers steel industry models in HO scale and N scale, since most of my clients want to at least start with these kits as a basis for their modeling.

So I'm really grateful that the NMRA arranged for the reprinting of Dean Freytag's The History, Making and Modeling of Steel. It also helps that the book is very focused on the Walthers steel industry models in HO scale and N scale, since most of my clients want to at least start with these kits as a basis for their modeling.(Between the time I started writing this blog entry and today, I discover that the book is sold out at the NMRA -- sorry about that. Perhaps interested readers will be able to find it from other sources or through inter-library loan.)

One of the nice things about Freytag's approach in the book is that he offers a lot of variations. Whether the modeler's preference is for detailed prototype replication or something more casual, lots of space dedicated to the steel industry or just a corner of the layout, Freytag offers useful advice for all. And he offers these suggestions in a positive and encouraging way that many modelers will find motivational.

Another very helpful part of the book is its focus on explaining in some (although not excruciating) detail the steel making process. Even this modest amount of background makes obvious the flaws in many steel-oriented published track plans.

I understand Bernie Kempinski has a book on the steel industry in the publication process and I'm sure that will be a good resource as well. But I wanted to take a moment to acknowledge Dean Freytag's excellent scholarship and spot-on writing tone, perfect for the modeler. Hopefully the book will become more readily available again.

I've written before about Allman Brothers member and recent Eric Clapton sideman Derek Trucks. I've been enjoying the Derek Trucks Band's most recent album, Already Free. Although the jazz and world music elements are still evident in Trucks' fabulous slide guitar sound, this album seems to me to have more blues and rock influence. Whether it's the easy acoustic shuffle that phases into a driving electric rock riff in "Down in the Flood" or the greasy slide that powers "Get What you Deserve", many of the tunes show a bit more muscle this time out.

I've written before about Allman Brothers member and recent Eric Clapton sideman Derek Trucks. I've been enjoying the Derek Trucks Band's most recent album, Already Free. Although the jazz and world music elements are still evident in Trucks' fabulous slide guitar sound, this album seems to me to have more blues and rock influence. Whether it's the easy acoustic shuffle that phases into a driving electric rock riff in "Down in the Flood" or the greasy slide that powers "Get What you Deserve", many of the tunes show a bit more muscle this time out. Also welcome to my ears are the vocal contributions of Clapton bandmate Doyle Bramhall II (who also wrote and produced some songs on the album) and Trucks' talented wife Susan Tedeschi. While I enjoy regular vocalist Mike Mattison, I find the variety of vocal styles really accents the wide range of Trucks' playing in this, my favorite Derek Trucks album to date.

Monday, February 01, 2010

MRP 2010 -- The "Lost Photos"

I am very pleased to have two of my layout designs featured in Model Railroad Planning 2010. The first track plan is part of a very interesting article on the Richmond Pacific Railroad (RPR) by lead author Bill Kaufman.

I am very pleased to have two of my layout designs featured in Model Railroad Planning 2010. The first track plan is part of a very interesting article on the Richmond Pacific Railroad (RPR) by lead author Bill Kaufman.The RPR was the subject of our Layout Design Challenge at the Bay Area SIG Meet in 2006. Different designers prepared versions of the RPR (or its predecessor Parr Terminal RR) for presentation and discussion at the meeting, in one of three defined areas. The MRP article combines a discussion of today's RPR with a number of those layout designs and a brief description of each by the designer.

My own contribution is a portable N scale switching layout based on the Parr Terminal and sized to fit on two standard folding banquet tables. Editor Tony Koester and the team at Kalmbach did a great job of turning a slightly clumsy collection of materials into a well-presented article.

For my second article ("Dallas on a Door") … well, let's just say that not all articles go even that smoothly. The compact N scale design captures key elements of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas ("The Katy" or M-K-T) in downtown Dallas on a hollow core door in N scale. Neat prototype, great client, nifty compact switching design. So far, so good.

But finding photos to illustrate the article proved to be much more difficult than expected. There were plenty of images on-line (like the one to the right). But locating photographers, clearing copyrights, and obtaining high-quality versions of the images proved daunting.

In the end, Kalmbach had to substitute some on-file material to help illustrate the article. Frustrating! (Now, I'm sure it's not just me that Editor Koester is writing about in his MRP 2010 editorial when he admonishes prospective authors about having their photos lined up before submitting. At least, I hope it's not just me!)

Oh, and sorry about that, Tony!

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Track Plan Triage

For about the last year, I have been working on a web-based introduction to track planning and layout design. Because this is a low priority and I've been busy with clients' projects, it may be another year (or more!) before it's published.

But as part of this effort, I've been thinking more about what newcomers to the hobby and to layout design are really asking for when they pop up on forums and elsewhere looking for help. (I'm talking about absolute newcomers here, not folks who've been around the hobby for a while and have learned about their own preferences, even if they don't yet have a layout.)

What makes a layout interesting varies

Like many others, my tendency is to try to help these complete newbies understand what makes a layout more engaging in the long run and explain why an oval with one siding and two spurs may soon prove tedious. As I've said before, I've seen a lot of these "Plywood Pacifics" gathering dust in a corner of the garage or basement after their builders abandoned them due to an excess of boredom and a shortage of fun.

My take-away is this: For many people, there needs to be more than just the most basic layout to offer interest and challenge to make the hobby rewarding in the long term. So my advice to newcomers has always been oriented toward pushing them in the direction of more potential and flexibility in a layout selection or the layout design process.

But I must recognize that not everyone needs the long term challenge of a layout designed for purposeful operations or even realistic scenery. Some people really do want to watch a couple of trains orbit around and around. Maybe occasionally build a new train in the yard or drop off a car here and there, but mostly just watch trains running round and round.

"No, more operation"

This became even clearer to me a few months ago when a fellow emailed me asking about "adding more operation" to one of the layouts in my layout design gallery. He is a friend of a friend, so I invested some time in suggesting adding more staging, or looking at additional car-spotting challenge with "sure spots".

But he seemed puzzled by my suggestions. "No," he said, "what I want is more operation -- more trains running at once." Then the light went on for me. When I suggested that we add a second main-line route so that he could have two trains orbiting simultaneously, he was thrilled and happily went off to build.

Track plan "triage"

So perhaps what's needed when we offer advice and suggestions to an absolute newcomer is to do a sort of triage on the request. Somehow we need to determine which requesters really will be happy in the long term with two trains running laps like obsessive-compulsive Olympians and which ones are asking for that only because they've never been exposed to the more engaging alternatives.

Some folks (probably a small minority, but maybe not) simply need to be pointed toward a decent multi-loop plan, offered a brief description of the more interesting alternatives for future reference, and then encouraged to go forth and orbit. Weighing these happy loopers down with discussions of staging, operations, and LDEs is probably not helping them enjoy the hobby the way they wish to enjoy it.

Others, whose interest may be piqued by opportunities for realistic scenes and/or purposeful operations, should be encouraged to look beyond the simple ovals and dogbones for a layout design that will offer more long-term involvement.

That process of triage, of quickly sorting the different help-seekers from one another, is the challenge -- one I haven't yet fully thought through. But perhaps all of us who offer advice to newcomers should try to be more sensitive to where these newbies are coming from and to whence they aspire. One size does not fit all.

But as part of this effort, I've been thinking more about what newcomers to the hobby and to layout design are really asking for when they pop up on forums and elsewhere looking for help. (I'm talking about absolute newcomers here, not folks who've been around the hobby for a while and have learned about their own preferences, even if they don't yet have a layout.)

What makes a layout interesting varies

Like many others, my tendency is to try to help these complete newbies understand what makes a layout more engaging in the long run and explain why an oval with one siding and two spurs may soon prove tedious. As I've said before, I've seen a lot of these "Plywood Pacifics" gathering dust in a corner of the garage or basement after their builders abandoned them due to an excess of boredom and a shortage of fun.

My take-away is this: For many people, there needs to be more than just the most basic layout to offer interest and challenge to make the hobby rewarding in the long term. So my advice to newcomers has always been oriented toward pushing them in the direction of more potential and flexibility in a layout selection or the layout design process.

But I must recognize that not everyone needs the long term challenge of a layout designed for purposeful operations or even realistic scenery. Some people really do want to watch a couple of trains orbit around and around. Maybe occasionally build a new train in the yard or drop off a car here and there, but mostly just watch trains running round and round.

"No, more operation"

This became even clearer to me a few months ago when a fellow emailed me asking about "adding more operation" to one of the layouts in my layout design gallery. He is a friend of a friend, so I invested some time in suggesting adding more staging, or looking at additional car-spotting challenge with "sure spots".

But he seemed puzzled by my suggestions. "No," he said, "what I want is more operation -- more trains running at once." Then the light went on for me. When I suggested that we add a second main-line route so that he could have two trains orbiting simultaneously, he was thrilled and happily went off to build.

Track plan "triage"

So perhaps what's needed when we offer advice and suggestions to an absolute newcomer is to do a sort of triage on the request. Somehow we need to determine which requesters really will be happy in the long term with two trains running laps like obsessive-compulsive Olympians and which ones are asking for that only because they've never been exposed to the more engaging alternatives.

Some folks (probably a small minority, but maybe not) simply need to be pointed toward a decent multi-loop plan, offered a brief description of the more interesting alternatives for future reference, and then encouraged to go forth and orbit. Weighing these happy loopers down with discussions of staging, operations, and LDEs is probably not helping them enjoy the hobby the way they wish to enjoy it.

Others, whose interest may be piqued by opportunities for realistic scenes and/or purposeful operations, should be encouraged to look beyond the simple ovals and dogbones for a layout design that will offer more long-term involvement.

That process of triage, of quickly sorting the different help-seekers from one another, is the challenge -- one I haven't yet fully thought through. But perhaps all of us who offer advice to newcomers should try to be more sensitive to where these newbies are coming from and to whence they aspire. One size does not fit all.

Wednesday, January 06, 2010

Black Diamonds and Beer

My latest article in the commercial press is a track plan for a modern-era shortline in N scale. The Schuylkill Haven Railroad is a proto-freelanced modern-day anthracite hauler in east-central Pennsylvania.

My latest article in the commercial press is a track plan for a modern-era shortline in N scale. The Schuylkill Haven Railroad is a proto-freelanced modern-day anthracite hauler in east-central Pennsylvania.The model layout is inspired by the real-life regional railroad Reading & Northern (RBMN). Proto-freelancing offered some welcome flexibility in combining attractive elements from the good-sized regional into the available space.

The track plan, photos, and a description of the design are found in the January/February 2010 issue of Model Railroad Hobbyist media-zine, always free for download here. View the track plan in my Design Gallery.

The track plan, photos, and a description of the design are found in the January/February 2010 issue of Model Railroad Hobbyist media-zine, always free for download here. View the track plan in my Design Gallery.

The design is based on a hybrid loop-to-oval out-and-back schematic, with key industries (coal tipple and truck dump, a plastics manufacturer, and a large brewery) located on branches from the main continuous running track. The RBMN operates tourist passenger service on some parts of its system, so that's also an option for some variety.

My client was already wisely looking at along-the-wall designs (rather than rectangles) when he contacted me, so the final design makes great use of the layout space. It was a fun project to develop with him and it's great to see it "in print" in MRH.

My client was already wisely looking at along-the-wall designs (rather than rectangles) when he contacted me, so the final design makes great use of the layout space. It was a fun project to develop with him and it's great to see it "in print" in MRH.

Friday, January 01, 2010

Theory vs. Practice #1 -- Yard Leads

The first in an occasional series of postings on what Internet blowhards say vs. what has actually been found to work. [Many of these "experts" haven't built their layout yet, of course, so they are free to opine without the inconvenient reality of experience.]

Theory: Many real-life railroad yards did not have separate yard leads, so they don't belong on model yards. Anyone who uses yard leads is simply following what other modelers have done like a bunch of brainless lemmings.

Practical experience: After one has helped build layouts, design layouts, and operated on many layouts, one will observe that most model railroaders run much larger numbers of trains in a given period of time through a given physical plant than would the real-life railroad. Yard leads are thus a concession to this density of traffic, necessary to keep these high levels of traffic flowing through yards and onto our always-too-short main lines.

The presence of yard leads on many successful layouts is an indication of their utility, not a case of mindless lock-step copying.

Verdict: Except for very low-density one- or two-train-per-day branch lines and terminal switching layouts, yard leads are often worth considering to ease traffic flow and allow more operators to have more fun on a given physical plant in the model -- especially given our short main line runs.

---

Hey, if you want to model bollixed-up yards and have your operators standing around twiddling their thumbs, more power to ya'. I'd rather have the traffic flow -- call me crazy!

Don't know what constitutes a yard lead?

A yard lead extends the opposite direction from a yard ladder, allowing a switcher to work without fouling the main. Note the crossover that allows trains to enter/exit the yard from the main.

The yard lead may connect back into the main at the far end (to the left in this sketch) to allow an additional path into and out of the yard when things are congested, but that is optional.

Craig Bisgeier's site explains in more detail.

Theory: Many real-life railroad yards did not have separate yard leads, so they don't belong on model yards. Anyone who uses yard leads is simply following what other modelers have done like a bunch of brainless lemmings.

Practical experience: After one has helped build layouts, design layouts, and operated on many layouts, one will observe that most model railroaders run much larger numbers of trains in a given period of time through a given physical plant than would the real-life railroad. Yard leads are thus a concession to this density of traffic, necessary to keep these high levels of traffic flowing through yards and onto our always-too-short main lines.

The presence of yard leads on many successful layouts is an indication of their utility, not a case of mindless lock-step copying.

Verdict: Except for very low-density one- or two-train-per-day branch lines and terminal switching layouts, yard leads are often worth considering to ease traffic flow and allow more operators to have more fun on a given physical plant in the model -- especially given our short main line runs.

---

Hey, if you want to model bollixed-up yards and have your operators standing around twiddling their thumbs, more power to ya'. I'd rather have the traffic flow -- call me crazy!

Don't know what constitutes a yard lead?

A yard lead extends the opposite direction from a yard ladder, allowing a switcher to work without fouling the main. Note the crossover that allows trains to enter/exit the yard from the main.

The yard lead may connect back into the main at the far end (to the left in this sketch) to allow an additional path into and out of the yard when things are congested, but that is optional.

Craig Bisgeier's site explains in more detail.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)