The other is an HO layout of a specific real-life railroad, locale, and era. The space is large, but irregular, with a number of doors, obstructions, and areas that must be kept clear. On-hand engines are finicky, so larger radii and turnouts are the order of the day.

The common link between these two projects for me? Constraints -- those sometimes-frustrating “givens” that one must deal with in coaxing a satisfying layout into a specific space. With the traditional design, it was a matter of managing radii, track-to-track spacing, and (especially) grades, all the while creating enough "breathing room" for some operating interest, scenic opportunities and some on-hand structure kits. An inch or two can mean a lot.

In the larger prototype-based layout, we’re trying to balance the desire for somewhat accurately depicting a number of scenes over nearly 200 miles of real-life railroad within the realities of finite space and the minimum radius demanded by the brass locomotives. The optimal location for a turnback loop squeezes aisles and adjoining benchwork uncomfortably. Here, too, an inch or two can mean a lot.

In turns out that I really enjoy working through these kinds of challenges. (Good thing, too, because they seem to crop up in every project.) It’s hard for me to relate to the interest some find in crafting pie-in-the-sky plans for oversized spaces they’ll never actually have. What’s the fun of layout design in a gymnasium? (Check that, if you happen to have a gymnasium, I’m available and happy to help.) To me, it’s exciting to finally come upon a great way to coil things into the space after trying a lot of alternatives and to suddenly see opportunities for locating specific scenes at an appropriate bend in the resulting benchwork footprint.

Working with constraints makes you clever, I think. Experts in brain morphology and function tell us that exercising our brains in different and challenging ways helps our brains stay younger. My layout design gray matter is getting a pretty good workout lately – gotta feel the burn.

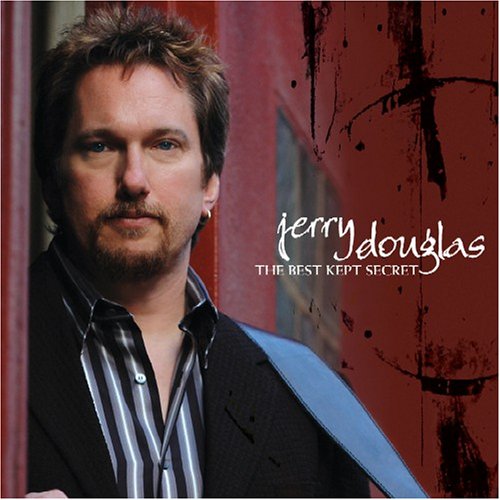

I had the chance a few weeks ago to hear dobro master Jerry Douglas in concert. His music defies categorization to some degree, but springs from bluegrass roots (as evidenced by his long-standing collaboration with Alison Krauss and Union Station). His band was first class (but why do the lead guitar players always have it cranked up to 11, no matter the venue?) and Douglas has a very dry sense of humor that illuminated some of the playful spirit in his tunes. He is widely regarded as the best to ever play the instrument, and it was a joy to experience the virtuosity in real life. The new CD is titled Best Kept Secret and goes a bit more in a jazz direction than some of his earlier work. I’m slightly more partial to the more blues- and bluegrass-inflected albums, but it’s still a keeper!

I had the chance a few weeks ago to hear dobro master Jerry Douglas in concert. His music defies categorization to some degree, but springs from bluegrass roots (as evidenced by his long-standing collaboration with Alison Krauss and Union Station). His band was first class (but why do the lead guitar players always have it cranked up to 11, no matter the venue?) and Douglas has a very dry sense of humor that illuminated some of the playful spirit in his tunes. He is widely regarded as the best to ever play the instrument, and it was a joy to experience the virtuosity in real life. The new CD is titled Best Kept Secret and goes a bit more in a jazz direction than some of his earlier work. I’m slightly more partial to the more blues- and bluegrass-inflected albums, but it’s still a keeper!